Myasthenia gravis

| Myasthenia gravis | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

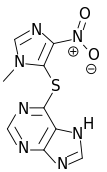

Detailed view of a neuromuscular junction: 1. Presynaptic terminal 2. Sarcolemma 3. Synaptic vesicle 4. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor 5. Mitochondrion |

|

| ICD-10 | G70.0 |

| ICD-9 | 358.0 |

| OMIM | 254200 |

| DiseasesDB | 8460 |

| MedlinePlus | 000712 |

| eMedicine | neuro/232 emerg/325 (emergency), med/3260 (pregnancy), oph/263 (eye) |

| MeSH | D009157 |

Myasthenia gravis (from Greek μύς "muscle", ἀσθένεια "weakness", and Latin gravis "serious"; abbreviated MG) is an autoimmune neuromuscular disease leading to fluctuating muscle weakness and fatiguability. It is an autoimmune disorder, in which weakness is caused by circulating antibodies that block acetylcholine receptors at the post-synaptic neuromuscular junction,[1] inhibiting the stimulative effect of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine. Myasthenia is treated medically with cholinesterase inhibitors or immunosuppressants, and, in selected cases, thymectomy. At 200–400 cases per million it is one of the less common autoimmune disorders [1]. MG must be distinguished from congenital myasthenic syndromes that can present similar symptomatology but offer no response to immunosuppressive interventions.

Contents |

Classification

The most widely accepted classification of myasthenia gravis is the Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America Clinical Classification:[2]

- Class I: Any eye muscle weakness, possible ptosis, no other evidence of muscle weakness elsewhere

- Class II: Eye muscle weakness of any severity, mild weakness of other muscles

- Class IIa: Predominantly limb or axial muscles

- Class IIb: Predominantly bulbar and/or respiratory muscles

- Class III: Eye muscle weakness of any severity, moderate weakness of other muscles

- Class IIIa: Predominantly limb or axial muscles

- Class IIIb: Predominantly bulbar and/or respiratory muscles

- Class IV: Eye muscle weakness of any severity, severe weakness of other muscles

- Class IVa: Predominantly limb or axial muscles

- Class IVb: Predominantly bulbar and/or respiratory muscles (Can also include feeding tube without intubation)

- Class V: Intubation needed to maintain airway

Signs and symptoms

The hallmark of myasthenia gravis is fatiguability. Muscles become progressively weaker during periods of activity and improve after periods of rest. Muscles that control eye and eyelid movement, facial expressions, chewing, talking, and swallowing are especially susceptible. The muscles that control breathing and neck and limb movements can also be affected. Often the physical examination yields results within normal limits.[3]

The onset of the disorder can be sudden. Often symptoms are intermittent. The diagnosis of myasthenia gravis may be delayed if the symptoms are subtle or variable.

In most cases, the first noticeable symptom is weakness of the eye muscles. In others, difficulty in swallowing and slurred speech may be the first signs. The degree of muscle weakness involved in MG varies greatly among patients, ranging from a localized form that is limited to eye muscles (ocular myasthenia), to a severe and generalized form in which many muscles - sometimes including those that control breathing - are affected. Symptoms, which vary in type and severity, may include asymmetrical ptosis (a drooping of one or both eyelids), diplopia (double vision) due to weakness of the muscles that control eye movements, an unstable or waddling gait, weakness in arms, hands, fingers, legs, and neck, a change in facial expression, dysphagia (difficulty in swallowing), shortness of breath and dysarthria (impaired speech, often nasal due to weakness of the velar muscles).

In myasthenic crisis a paralysis of the respiratory muscles occurs, necessitating assisted ventilation to sustain life. In patients whose respiratory muscles are already weak, crises may be triggered by infection, fever, an adverse reaction to medication, or emotional stress.[4] Since the heart muscle is only regulated by the autonomic nervous system, it is generally unaffected by MG.

Pathophysiology

Myasthenia gravis is an autoimmune channelopathy: it features antibodies directed against the body's own proteins. While various similar diseases have been linked to immunologic cross-reaction with an infective agent, there is no known causative pathogen that could account for myasthenia. There is a slight genetic predisposition: particular HLA types seem to predispose for MG (B8 and DR3 with DR1 more specific for ocular myasthenia). Up to 75% of patients have an abnormality of the thymus; 25% have a thymoma, a tumor (either benign or malignant) of the thymus, and other abnormalities are frequently found. The disease process generally remains stationary after thymectomy (removal of the thymus).

In MG, the auto-antibodies most commonly against the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR)[5] , the receptor in the motor end plate for the neurotransmitter acetylcholine that stimulates muscular contractions. Some forms of the antibody impair the ability of acetylcholine to bind to receptors. Others lead to the destruction of receptors, either by complement fixation or by inducing the muscle cell to eliminate the receptors through endocytosis.

The antibodies are produced by plasma cells, derived from B-cells. B-cells convert into plasma cells by T-helper cell stimulation. In order to carry out this activation, T-helpers must first be activated themselves, which is done by binding of the T-cell receptor (TCR) to the acetylcholine receptor antigenic peptide fragment (epitope) resting within the major histocompatibility complex of an antigen presenting cells. Since the thymus plays an important role in the development of T-cells and the selection of TCR myasthenia gravis is closely associated with thymoma . The exact mechanisms are however not convincingly clarified although resection of the thymus (thymectomy) in MG patients without a thymus neoplasm often have positive results.

In normal muscle contraction, cumulative activation of the nAChR leads to influx of sodium ions which in turn causes the depolarization of muscle cell and subsequent opening of voltage gated sodium channels. This ion influx then travels down the cell membranes via T-tubules and, via calcium channel complexes leads to the release of calcium from the sarcoplasmic reticulum. Only when the levels of calcium inside the muscle cell are high enough will it contract. Decreased numbers of functioning nAChRs therefore impairs muscular contraction by limiting depolarization. In fact, MG causes the motor neuron action potential to muscular twitch ratio to vary from the non-pathological one to one ratio.

It has recently been realized that a second category of gravis is due to auto-antibodies against the MuSK protein (muscle specific kinase), a tyrosine kinase receptor which is required for the formation of the neuromuscular junction. Antibodies against MuSK inhibit the signaling of MuSK normally induced by its nerve-derived ligand, agrin. The result is a decrease in patency of the neuromuscular junction, and the consequent symptoms of MG.

People treated with penicillamine can develop MG symptoms. Their antibody titer is usually similar to that of MG, but both the symptoms and the titer disappear when drug administration is discontinued.

MG is more common in families with other autoimmune diseases. A familial predisposition is found in 5% of the cases. This is associated with certain genetic variations such as an increased frequency of HLA-B8 and DR3. People with MG suffer from co-existing autoimmune diseases at a higher frequency than members of the general population. Of particular mention is co-existing thyroid disease where episodes of hypothyroidism may precipitate a severe exacerbation.

The acetylcholine receptor is clustered and anchored by the Rapsyn protein, research in which might eventually lead to new treatment options.[6]

Associated condition

Myasthenia Gravis is associated with various autoimmune diseases[7], including:

- Thyroid diseases, including Hashimoto's thyroiditis and Graves' disease

- Diabetes mellitus type 1

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Lupus, and

- Demyelinating CNS diseases

Seropositive and "double-seronegative" patients often have thymoma or thymic hyperplasia. However, anti-MuSK positive patients do not have evidence of thymus pathology.

In pregnancy

In the long term, pregnancy does not affect myasthenia gravis. Up to 10% of infants with parents affected by the condition are born with transient (periodic) neonatal myasthenia (TNM) which generally produces feeding and respiratory difficulties.[8] TNM usually presents as poor sucking and generalized hypotonia (low muscle tone). Other reported symptoms include a weak cry, facial diplegia (paralysis of one part of the body) or paresis (impaired or lack of movement) and mild respiratory distress. A child with TNM typically responds very well to acetylcholinesterase inhibitors. The mothers themselves suffer from exacerbated myasthenia in a third of cases and in those for whom it does worsen, it usually occurs in the first trimester of pregnancy. Signs and symptoms in pregnant mothers tend to improve during the second and third trimester. Complete remission can occur in some mothers.[9] Immunosuppressive therapy should be maintained throughout pregnancy as this reduces the chance of neonatal muscle weakness, as well as controlling the mother's myasthenia.[8]

Very rarely, an infant can be born with arthrogryposis multiplex congenita, secondary to profound intrauterine weakness. This is due to maternal antibodies that target an infant's acetylcholine receptors. In some cases, the mother remains asymptomatic.[8]

Diagnosis

Myasthenia can be a difficult diagnosis, as the symptoms can be subtle and hard to distinguish from both normal variants and other neurological disorders.[3] A thorough physical examination can reveal easy fatiguability, with the weakness improving after rest and worsening again on repeat of the exertion testing. Applying ice to weak muscle groups characteristically leads to improvement in strength of those muscles. Additional tests are often performed, as mentioned below. Furthermore, a good response to medication can also be considered a sign of autoimmune pathology.

Physical examination

Muscle fatigability can be tested for many muscles.[10] A thorough investigation includes:

- looking upward and sidewards for 30 seconds: ptosis and diplopia.

- looking at the feet while lying on the back for 60 seconds

- keeping the arms stretched forward for 60 seconds

- 10 deep knee bends

- walking 30 steps on both the toes and the heels

- 5 situps, lying down and sitting up completely

- "Peek sign": after complete initial apposition of the lid margins, they quickly (within 30 seconds) start to separate and the sclera starts to show[3]

Blood tests

If the diagnosis is suspected, serology can be performed in a blood test to identify certain antibodies:

- One test is for antibodies against the acetylcholine receptor.[3] The test has a reasonable sensitivity of 80–96%, but in MG limited to the eye muscles (ocular myasthenia) the test may be negative in up to 50% of the cases.

- A proportion of the patients without antibodies against the acetylcholine receptor have antibodies against the MuSK protein.[11]

- In specific situations (decreased reflexes which increase on facilitation, co-existing autonomic features, suspected presence of neoplasm, especially of the lung, presence of increment or facilitation on repetitive EMG testing) testing is performed for Lambert-Eaton syndrome, in which other antibodies (against a voltage-gated calcium channel) can be found.

Neurophysiology

Muscle fibers of patients with MG are easily fatigued, and thus do not respond as well as muscles in healthy individuals to repeated stimulation. By repeatedly stimulating a muscle with electrical impulses, the fatiguability of the muscle can be measured. This is called the repetitive nerve stimulation test. In single fiber electromyography, which is considered to be the most sensitive (although not the most specific) test for MG,[3] a thin needle electrode is inserted into a muscle to record the electric potentials of individual muscle fibers. By finding two muscle fibers belonging to the same motor unit and measuring the temporal variability in their firing patterns (i.e. their 'jitter'), the diagnosis can be made.

Edrophonium test

The "edrophonium test" is infrequently performed to identify MG; its application is limited to the situation when other investigations do not yield a conclusive diagnosis. This test requires the intravenous administration of edrophonium chloride (Tensilon, Reversol) or neostigmine (Prostigmin), drugs that block the breakdown of acetylcholine by cholinesterase (cholinesterase inhibitors) and temporarily increases the levels of acetylcholine at the neuromuscular junction. In people with myasthenia gravis involving the eye muscles, edrophonium chloride will briefly relieve weakness.[12]

Imaging

A chest X-ray is frequently performed; it may point towards alternative diagnoses (e.g. Lambert-Eaton due to a lung tumor) and comorbidity. It may also identify widening of the mediastinum suggestive of thymoma, but computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are more sensitive ways to identify thymomas, and are generally done for this reason.[13]

Pulmonary function test

Spirometry (lung function testing) may be performed to assess respiratory function if there are concerns about a patient's ability to breathe adequately. The forced vital capacity may be monitored at intervals in order not to miss a gradual worsening of muscular weakness. Acutely, negative inspiratory force (NIF) may be used to determine adequacy of ventilation. Severe myasthenia may cause respiratory failure due to exhaustion of the respiratory muscles.[14]

Pathological findings

Muscle biopsy is only performed if the diagnosis is in doubt and a muscular condition is suspected. Immunofluorescence shows IgG antibodies on the neuromuscular junction. (Note that it is not the antibody which causes myasthenia gravis that fluoresces, but rather a secondary antibody directed against it.) Muscle electron microscopy shows receptor infolding and loss of the tips of the folds, together with widening of the synaptic clefts. Both these techniques are currently used for research rather than diagnostically.[6]

Treatment

Treatment is by medication and/or surgery. Medication consists mainly of cholinesterase inhibitors to directly improve muscle function and immunosuppressant drugs to reduce the autoimmune process. Thymectomy is a surgical method to treat MG. For emergency treatment, plasmapheresis or IVIG can be used as a temporary measure to remove antibodies from the blood circulation.

Medication

- Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors: neostigmine and pyridostigmine can improve muscle function by slowing the natural enzyme cholinesterase that degrades acetylcholine in the motor end plate; the neurotransmitter is therefore around longer to stimulate its receptor. Usually doctors will start with a low dose, e.g. 3x20mg pyridostigmine, and increase until the desired result is achieved. If taken 30 minutes before a meal, symptoms will be mild during eating. Side effects, like perspiration and diarrhea can be countered by adding atropine. Pyridostigmine is a short-lived drug with a half-life of about 4 hours.

- Immunosuppressive drugs: prednisone, cyclosporine, mycophenolate mofetil and azathioprine may be used. It is common for patients to be treated with a combination of these drugs with a cholinesterase inhibitor. Treatments with some immunosuppressives take weeks to months before effects are noticed. Other immunomodulating substances, like drugs preventing acetylcholine receptor modulation by the immune system are currently being researched[15]

Plasmapheresis and IVIG

If the myasthenia is serious (myasthenic crisis), plasmapheresis can be used to remove the putative antibody from the circulation. Also, Intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIG) can be used to bind the circulating antibodies. Both of these treatments have relatively short-lived benefits, typically measured in weeks.[16]

Surgery

Thymectomy, the surgical removal of the thymus, is essential in cases of thymoma in view of the potential neoplastic effects of the tumor. However, the procedure is more controversial in patients who do not show thymic abnormalities. Although some of these patients improve following thymectomy, some patients experience severe exacerbations and the highly controversial concept of "therapeutic thymectomy" for patients with thymus hyperplasia is disputed by many experts and efforts are underway to unequivocally answer this important question.

There are a number of surgical approaches to the removal of the thymus gland: transsternal (through the sternum, or breast bone), transcervical (through a small neck incision), and transthoracic (through one or both sides of the chest). The transsternal approach is most common and uses the same length-wise incision through the sternum (breast bone)used for most open-heart surgery. The transcervical approach is a less invasive procedure that allows for removal of the entire thymus gland through a small neck incision. There has been no difference in success in symptom improvement between the transsternal approach and the minimally invasive transcervical approach.[17] However for patients with a thymoma it is important that all the tissue is removed as thymic tissue can regrow. Thymomas can be malignant and are thought to be the onset of other diseases as well. For this reason, many surgeons will only recommend the full sternotomy approach to a thymectomy.

Thymoma is relatively rare in younger (<40) patients, but paradoxically especially younger patients with generalized MG without thymoma benefit from thymectomy. Of course, resection is also indicated for those with a thymoma, but it is less likely to improve the MG symptoms.

Prognosis

With treatment, patients have a normal life expectancy, except for those with a malignant thymoma (whose lesser life expectancy is on account of the thymoma itself and is otherwise unrelated to the myasthenia). Quality of life can vary depending on the severity and the cause. The drugs used to control MG either diminish in effectiveness over time (cholinesterase inhibitors) or cause severe side effects of their own (immunosuppressants). A small percentage (around 10%) of MG patients are found to have tumors in their thymus glands, in which case a thymectomy is a very effective treatment with long-term remission. However, most patients need treatment for the remainder of their lives, and their abilities vary greatly. It should be noted that MG is not usually a progressive disease. The symptoms may come and go, but the symptoms do not always get worse as the patient ages. For some, the symptoms decrease after a span of 3–5 years.

Epidemiology

Myasthenia gravis occurs in all ethnic groups and both genders. It most commonly affects women under 40 - and people from 50 to 70 years old of either sex, but it has been known to occur at any age. Younger patients rarely have thymoma. The prevalence in the United States is estimated at 20 cases per 100,000.[18] Risk factors are the female gender with ages 20 – 40, familial myasthenia gravis, D-penicillamine ingestion (drug induced myasthenia), and having other autoimmune diseases.

Three types of myasthenic symptoms in children can be distinguished:[10]

- Neonatal: In 12% of the pregnancies with a mother with MG, she passes the antibodies to the infant through the placenta causing neonatal myasthenia gravis. The symptoms will start in the first two days and disappear within a few weeks after birth. With the mother it is not uncommon for the symptoms to even improve during pregnancy, but they might worsen after labor.

- Congenital: Children of a healthy mother can, very rarely, develop myasthenic symptoms beginning at birth. This is called congenital myasthenic syndrome or CMS. Other than myasthenia gravis, CMS is not caused by an autoimmune process, but due to synaptic malformation, which in turn is caused by genetic mutations. Thus, CMS is a hereditary disease. More than 11 different mutations have been identified and the inheritance pattern is typically autosomal recessive.

- Juvenile myasthenia gravis: myasthenia occurring in childhood but after the peripartum period.

The congenital myasthenias cause muscle weakness and fatigability similar to those of MG. The symptoms of CMS usually begin within the first two years of life, although in a few forms patients can develop their first symptoms as late as the seventh decade of life. A diagnosis of CMS is suggested by the following:

- Onset of symptoms in infancy or childhood.

- Weakness which increases as muscles tire.

- A decremental EMG response, on low frequency, of the compound muscle action potential (CMAP).

- No anti-AChR or MuSK antibodies.

- No response to immunosuppressant therapy.

- Family history of symptoms which resemble CMS.

The symptoms of CMS can vary from mild to severe. It is also common for patients with the same form, even members of the same family, to be affected to differing degrees. In most forms of CMS weakness does not progress, and in some forms, the symptoms may diminish as the patient gets older. Only rarely do symptoms of CMS become worse with time.

Notable patients

- Amitabh Bachchan, Bollywood superstar, voted Star of Millennium on BBC.

- Gregory Chudnovsky, mathematician

- Brandon Cox, starting Auburn Quarterback from 2005-2007. Finished with a record of 29-9.

- Noah Dietrich

- Henrique Mecking, Brazilian chess grandmaster.

- Christopher Robin Milne, 1920–1996, of Winnie-the-Pooh fame and son of author A.A. Milne.

- Aristotle Onassis, Greek shipbuilder and husband of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis.

- Augustus Pablo, reggae musician. Died May 18, 1999 due to a collapsed lung having suffered from the disease for some time.

- Suzanne Rogers, Emmy award winning daytime television actress; plays Maggie Horton on Days of our Lives. Diagnosed in 1984, but currently in remission; her condition was dramatized on the series as her character was shown to be suffering from it as well.

- Roger Smith, semi-retired actor/talent manager, husband of Ann-Margret.

- John Spencer (snooker player) , World professional snooker champion 1969, 1971 and 1977. Double vision, associated with the disease, effectively ended his career in the mid 1980s.

- Vijay Tendulkar, a renowned Indian playwright; died May 19, 2008 due to complications arising out of myasthenia gravis.

- Mary Broadfoot Walker, British physician who first discovered the effectiveness of physostigmine in the treatment of myasthenia gravis.

- Madame Web, a fictional character from the Spider-Man comics and other media.

- Static Major, an R&B singer/songwriter, died February 2008 due to complications

- Waldo Farthingwaite-Jones Fictional character from Robert A. Heinlein's short story Waldo, who overcomes Myasthenia Gravis through the use of highly specialized remote manipulators and logically consistent magic.[19]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Conti-Fine BM, Milani M, Kaminski HJ (2006). "Myasthenia gravis: past, present, and future". J. Clin. Invest. 116 (11): 2843–54. doi:10.1172/JCI29894. PMID 17080188.

- ↑ Jaretzki A, Barohn RJ, Ernstoff RM, et al. (2000). "Myasthenia gravis: recommendations for clinical research standards. Task Force of the Medical Scientific Advisory Board of the Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America". Neurology 55 (1): 16–23. PMID 10891897. http://www.neurology.org/cgi/content/full/55/1/16.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Scherer K, Bedlack RS, Simel DL. (2005). "Does this patient have myasthenia gravis?". JAMA 293 (15): 1906–14. doi:10.1001/jama.293.15.1906. PMID 15840866.

- ↑ Bedlack RS, Sanders DB. (2000). "How to handle myasthenic crisis. Essential steps in patient care.". Postgrad Med 107 (4): 211–4, 220–2. PMID 10778421. http://www.postgradmed.com/issues/2000/04_00/bedlack.htm.

- ↑ Patrick J, Lindstrom J. Autoimmune response to acetylcholine receptor. Science (1973) 180:871–2.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Losen M, Stassen MH, Martínez-Martínez P, et al. (2005). "Increased expression of rapsyn in muscles prevents acetylcholine receptor loss in experimental autoimmune myasthenia gravis". Brain 128 (Pt 10): 2327–37. doi:10.1093/brain/awh612. PMID 16150851.

- ↑ S. Thorlacius et al., “Associated disorders in myasthenia gravis: autoimmune diseases and their relation to thymectomy,” Acta Neurologica Scandinavica 80, no. 4 (1989): 290-295.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Warrell, David A; Timothy M Cox, et al. (2003). Oxford Texbook of Medicine — Fourth Edition — Volume 3. Oxford. pp. 1170. ISBN 0-19852787-X.

- ↑ Téllez-Zenteno JF, Hernández-Ronquillo L, Salinas V, Estanol B, da Silva O (2004). "Myasthenia gravis and pregnancy: clinical implications and neonatal outcome". BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders 5: 42. doi:10.1186/1471-2474-5-42. PMID 15546494. PMC 534111. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2474/5/42. Retrieved 2008-07-10.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Baets, M.H.; H.J.G.H. Oosterhuis (1993). Myasthenia gravis. DRD Press. pp. 158. ISBN 3805547366.

- ↑ Leite MI, Jacob S, Viegas S, et al. (July 2008). "IgG1 antibodies to acetylcholine receptors in 'seronegative' myasthenia gravis". Brain 131 (Pt 7): 1940–52. doi:10.1093/brain/awn092. PMID 18515870. PMC 2442426. http://brain.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=18515870.

- ↑ Seybold ME (1986). "The office Tensilon test for ocular myasthenia gravis". Arch Neurol 43 (8): 842–3. PMID 3729766.

- ↑ de Kraker M, Kluin J, Renken N, Maat AP, Bogers AJ (2005). "CT and myasthenia gravis: correlation between mediastinal imaging and histopathological findings". Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 4 (3): 267–71. doi:10.1510/icvts.2004.097246. PMID 17670406.

- ↑ Thieben MJ, Blacker DJ, Liu PY, Harper CM Jr, Wijdicks EF (2005). "Pulmonary function tests and blood gases in worsening myasthenia gravis". Muscle Nerve 32 (5): 664–667. doi:10.1002/mus.20403. PMID 16025526.

- ↑ Losen M, Martínez-Martínez P, Phernambucq M, Schuurman J, Parren PW, DE Baets MH (2008). "Treatment of myasthenia gravis by preventing acetylcholine receptor modulation". Ann N Y Acad Sci 1132: 174–9. doi:10.1196/annals.1405.034. PMID 18567867.

- ↑ Juel VC. (2004). "Myasthenia gravis: management of myasthenic crisis and perioperative care.". Semin Neurol 24 (1): 75–81. doi:10.1055/s-2004-829595. PMID 15229794.

- ↑ Calhoun R, et al. (1999). "Results of transcervical thymectomy for myasthenia gravis in 100 consecutive patients.". Annals of Surgery 230 (4): 555–561. doi:10.1097/00000658-199910000-00011. PMID 10522725.

- ↑ "What is Myasthenia Gravis (MG)?". Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America. http://www.myasthenia.org/amg_whatismg.cfm.

- ↑ Heinlein, Robert A. (1942). Waldo.

External links

- The Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America

- The Myasthenia Gravis Association (MGA) in the United Kingdom & the Republic of Ireland

- The Myasthenia Gravis Coalition of Canada

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||